- The registration procedure should be digitalised as much as possible. This has been implemented by the ILT and will be further optimized. Via the ‘MijnILT’ portal, shipowners and ship managers can submit applications for certificates of registry and other certificates issued by the ILT. By now, all certificates can be applied for via this portal or separate web-based forms. This is a strong improvement in the process and reduces the administrative burden for the applicant and the risk of typing errors on the part of the ILT. However, tracking the status of ILT’s processing of the application is still missing from the portal.

- The processing time of an application with the ILT is currently around one week. This is substantially shorter than the many weeks to months that this process took in 2022 and acceptable. As of 2024, extra funds have been allocated to recruit additional personnel. This has led to a minimalization of the processing time. It is essential that this at least remains as it currently is. In comparison: the largest registries in the world can process applications within 24 or 48 hours. In the Dutch House of Representatives, the minister has previously indicated that 24 or 48 hours for a quality register like the Dutch one is difficult to achieve, but that (provisional) certificates of registry and declarations of nationality should in any case be issued within five working days. The KVNR hopes that processing times will remain as short as possible and, above all, that the extremely long processing times of 2022 will definitely be a thing of the past.

- The accessibility of the ILT is moderate. Using the general phone number, the registration desk is hard to reach by phone. Contact between applicants and ILT staff by e-mail is often one-to-one. This is not resilient and often increases the workload of ILT staff. If an employee leaves or is absent, emails are left unanswered and there is no back-up. Moreover, answering an e-mail is relatively time-consuming, while emails often consist of procedural questions from applicants (i.e. is my application complete, when can I expect my certificate of registry, etc.). These types of questions can be easily handled by running the process through the portal, as addressed in the point above.

- The advisory function of the Dutch Shipping Register can be further accomplished by the increased functionality of the portal. This is currently still lacking structure: there is no capacity available to advise potential ‘flag clients’ and to provide them with all the necessary information.

- Account management should help potential ‘flag clients’ to access the various organisations (ILT, the Dutch Cadastre, Land Registry and Mapping Agency, the Dutch Authority for Digital Infrastructure, KIWA) to obtain the necessary certificates and permits to sail under the Dutch flag. The current situation, namely the lack of account management, leads to frustration among ‘flag clients’. The KVNR is now taking on a large part of these queries, which is more out of necessity, as the ILT has stopped doing this. As is well known, the KVNR is certainly open to giving the KVNR a more structural role in this, which should lead to structural cooperation between the executor of the register and the KVNR.

- The capacity, in terms of staffing, of the ILT to fulfil its implementation tasks is still insufficient, as the above points illustrate. If the current scope of tasks remains the same and the measures identified by PwC are taken up, it is inevitable that capacity will have to be added structurally. In addition, the long lead times in 2022 demonstrated that structural capacity at the ILT is too limited, so that if one employee leaves, the system collapses like a house of cards.

- Responsibility is being shifted; the shipping register currently lacks authority. For policy, policy interpretation and implementation and enforcement purposes, this is an undesirable situation. Policy, implementation and enforcement – where the emphasis is on coordination between department and the ILT – always puts the ball in the other one’s court. It goes without saying that this situation can be resolved by taking a position, but of course the future of a register also depends on the content of this position.

For the sake of completeness, the KVNR notes here that the above not only applies to the Dutch shipping register, but should also apply as an objective for the Curaçao register.

Governance of the Dutch Shipping Register

In principle, the previous minister of Infrastructure and Water Management took a decision in November 2020 to establish a maritime authority, as a service component of the Directorate-General for Civil Aviation and Maritime Affairs (DGLM): in other words, a public variant.

At that time, the minister indicated to use the first half of 2021 to map out all aspects of the transformation of the shipping register – currently with the ILT – into a maritime authority. She also indicated that during these six months, the conditions that would need to be met by the maritime authority would be established. After that, there was a long silence. That is why the KVNR is making this appeal to political parties.

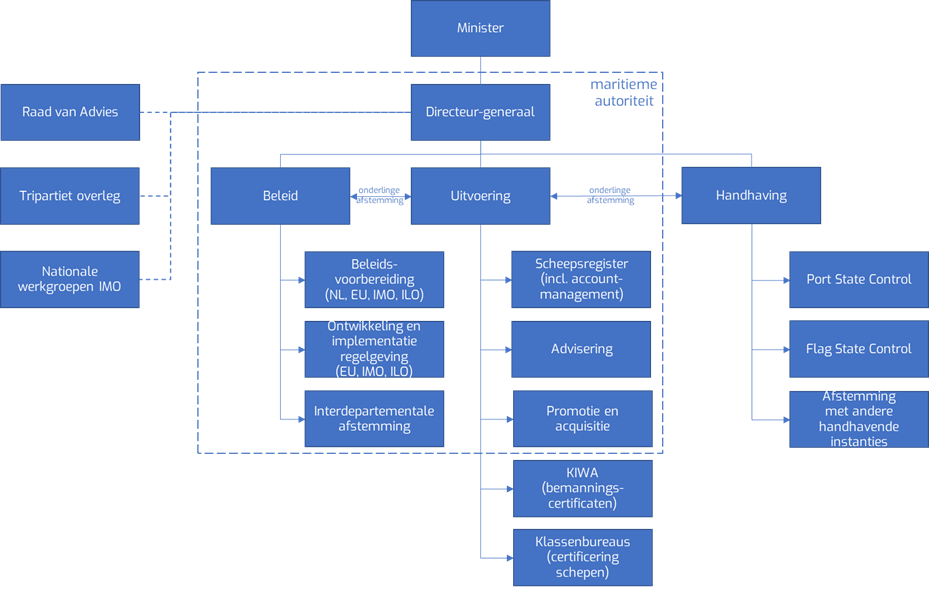

The KVNR envisions the maritime authority as follows (Dutch labels):

Contact with the market, which consists of many different sectors, must be ensured. The KVNR envisions this in the form of an advisory council. This council consists of representatives from the various market segments, which are involved with the maritime authority. This council can advise the maritime authority in both a solicited and unsolicited manner. On the subject of market developments, for example, which may require a shift in focus or the renewal or modification of policy. The maritime authority can also specifically ask the advisory council to advise on, for instance, the effectiveness of the organisation and whether it is in line with the competitive position of the maritime cluster at the international level. The already existing national working groups, in which the industry provides the authority with input for IMO meetings, and the tripartite consultations between authority, classification bureaus and industry, are highly appreciated by the industry and, as far as the KVNR is concerned, will continue to exist alongside an advisory council.

It goes without saying that the current tasks of the shipping register, now carried out by the ILT, will also be carried out by the maritime authority. This includes the:

- registration of ships under the Dutch flag,

- approval of crew plans,

- recognition of training courses and accreditation of training institutes,

- granting of exemptions and dispensations,

- support of Dutch-flagged ships at home and abroad,

- follow-up and handling of accidents and incidents on board Dutch-flagged seagoing vessels,

- management of mandated parties and (inter)national representation of the Dutch flag state,

- management of classification societies and Kiwa.

Supervision of certifying institutions

The latter is an area of concern. An interim report was recently published by the ILT, which revealed that the ILT’s supervision of certifying institutions, such as classification societies and Kiwa, is insufficient. The ILT is therefore unable to check whether the flag state tasks outsourced to classification societies and Kiwa are of sufficient quality. In fact, this report amounts to a cry for help from the ILT that it has too little capacity and thus financial resources at its disposal to properly carry out this supervisory task.

The opinion of the KVNR is that the maritime authority has an important role to play here. This will bring policy, implementation and enforcement and supervision closer together. By achieving better coordination between the various pillars (policy, implementation, enforcement and supervision), the industry’s knowledge within the authority will be better safeguarded. This will ultimately lead to an effective and intelligent maritime authority.

For the KVNR, it is beyond doubt that the tasks already outsourced to market parties, as described above, will also remain. After all, the quality of both the classification societies and Kiwa is good; the ILT itself questions its capacity to provide sufficient supervision.

Perhaps superfluously, specific attention has been given here to the implementation of the maritime authority from the perspective of the shipping industry. Fisheries, inland shipping, and recreational boating, which might also fall within the scope of the maritime authority, have not been considered.