In recent years, exhaust gas emissions originating from maritime traffic have sharply declined (CO2 emissions fell by 10% from 2007 to 2012). The combination of stricter regulations and innovations to reduce fuel consumption and thus emissions have been the main reasons for this reduction. The increasing size of ships and ‘slow steaming’ strategies have also had an effect in reducing the environmental footprint of shipping.

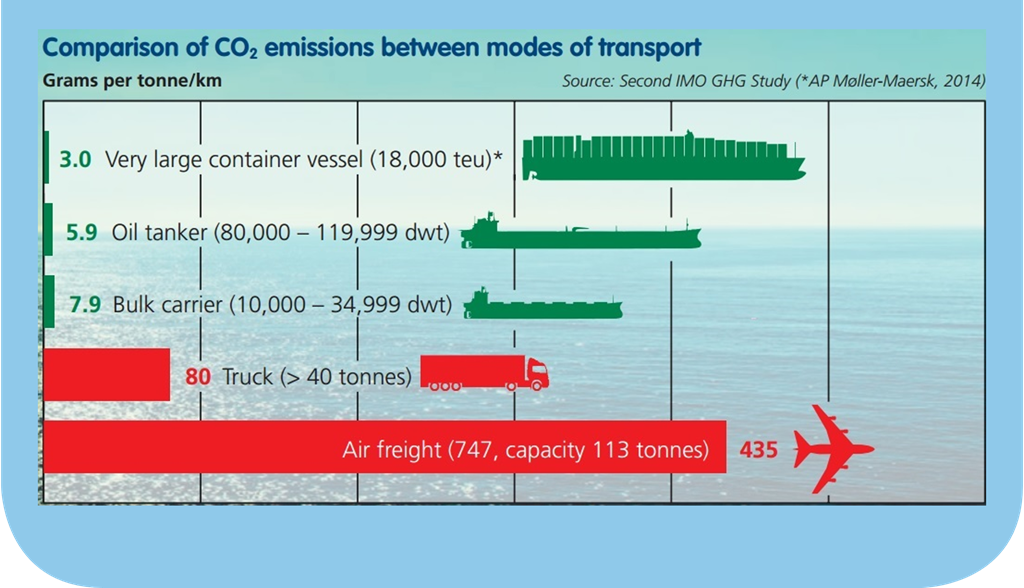

Here, when looking at CO2 emissions per tonne/kilometre, it should be noted that the shipping industry already compares favourably with aviation and road transport. For example, current CO2 emissions from shipping currently account for only 2.3% of total global CO2 emissions.

However, due to the anticipated further growth of world trade and the IMO climate agreement for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (aiming to halve emissions in 2050 compared to 2008), further steps are needed.

Some important measures have already been taken, and the shipping industry has undergone significant change. For example, since 1950, shipping has succeeded in reducing CO2 emissions per tonne/kilometre by 70%. The infographic above compares the CO2 emissions of various modes of transport.

Global standards for maximum energy consumption

Every new ship (or ship that is undergoing a major refit), must comply with an Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), the standards of which are gradually becoming stricter. An EEDI determines a vessel’s maximum permitted energy consumption, and therefore the maximum permitted level of CO2 emissions.

A Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) is also obligatory, ensuring that shipowners take operational measures to reduce the fuel consumption of their fleet. Logbooks must be used to record the environmental performance of vessels; a useful tool to make crews more aware of fuel-efficient operations.

IMO adopts compulsory global CO2 data collection system

UN Member States adopted the proposal for a mandatory global CO2 data collection system at the 70th meeting of the IMO Environment Committee (MEPC 70) in October 2016. This system should provide more awareness of the CO2 emissions of ships larger than 5,000 GT. Shipowners with such vessels monitor their CO2 emissions and deliver these data to the IMO. The data are then stored anonymously.

It is logical that the global CO2 data collection system focuses on ships larger than 5,000 GT because this category of ship is responsible for approximately 90% of the CO2 emissions from shipping. It also means that shipowners and captain-owners of smaller ships are not faced with additional administrative work. In recent years, the KVNR has expressed itself approval of such an IMO system.

There is also a European system, which entered force in July 2015. Called the European MRV (monitoring, reporting and verification) system, this obliges shipowners of vessels larger than 5,000 GT to monitor, report and have verified their CO2 emissions as of 1 January 2018.

Compared to the IMO system, this is a more complicated and also regional instrument for monitoring CO2 emissions. For example, the European system requires that the type of cargo transported must also be reported per trip. This, for much of the general cargo vessel fleet, varies greatly due to the sheer diversity and weight of transported cargoes.

For instance, one trip transports steel piping while the next carries wind turbine nacelles. The differences in weight mean that fuel consumption – and therefore CO2 emissions – vary enormously between the two journeys. This can quickly produce an inaccurate picture of the activities of these types of ships.

The KVNR believes that using two parallel systems is undesirable due to the increased administrative burden for shipowners. The KVNR is satisfied with the fact that IMO member states have agreed on a mandatory global data collection system, and advocates using one global system which is harmonised with the EU-MRV.

NOx

In 2014, the IMO Environmental Committee (MEPC 66) decided to implement the NOx Tier III standard in two pre-designated NOx Emission Control Areas (NECAs) for vessels built on or after 1 January 2016. The NECAs were located in United States and Caribbean coastal waters. The start date of construction is defined as the date of keel laying. Separate regulations applied to the North and Baltic Sea NECAs.

The KVNR is satisfied with the decision of North Sea countries to introduce stricter nitrogen standards (Tier III) in the North Sea at the same time as the Baltic Sea. The MEPC 70 in October 2016 unanimously approved this proposal. The proposed date that from which new ships must comply with the stricter NOx Tier III standard in these two European NECAs is 1 January 2021.

SOx

The sulphur content of marine fuels has been reduced in recent years. This will continue further in the years ahead. For example, permitted SOx levels in 2012 were 4.5%, compared to 3.5% now, and 0.5% in 2020.

Moreover, stricter standards have been enforced in specially designated areas since 1 January 2010. These areas are known as SECAs; Sulphur Emission Control Areas. Since 1 January 2015, a maximum sulphur content of 0.1% has been allowed in these areas. European SECAs comprise the North and Baltic Seas, and the English Channel. North American SECAs include 200 nautical miles from North American coasts and around the American Caribbean.

A maximum sulphur content of 0.1% has been enforced in European ports for docked vessels since 1 January 2010.